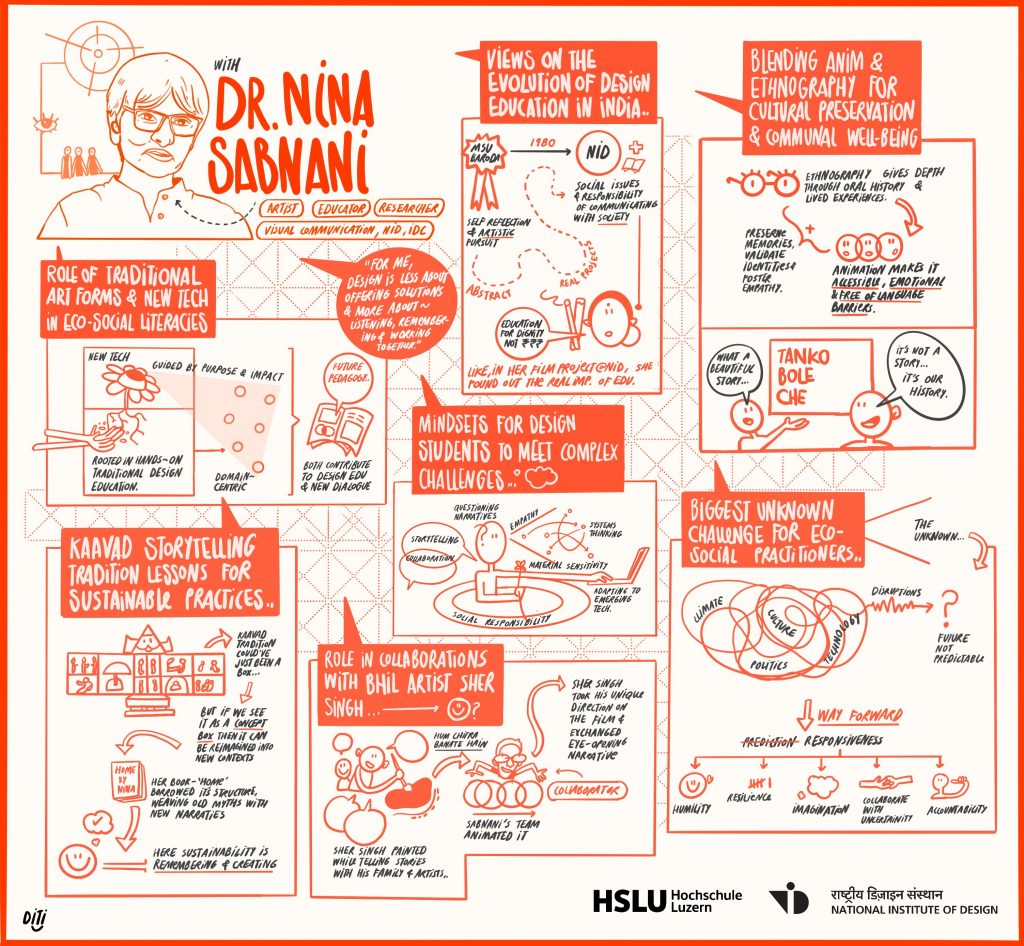

In this conversation, artist, educator, and researcher Nina Sabnani traces how storytelling, craft, and collaboration can anchor eco-social design education. Drawing on decades at NID and IDC, where she co-founded the Animation curriculum (1985) and later coordinated New Media Design, Sabnani argues for curricula that connect ethnography and material culture with community-rooted practice. We discuss how animated films and illustrated books can hold social memory and dissent—from Mukund and Riaz (partition through textile art) to Shubh Vivah (anti-dowry via Madhubani). She reflects on working with traditional artists and sustainable livelihoods, including research on the Kaavad storytelling tradition and films such as Tanko Bole Chhe (The Stitches Speak) and Hum Chitra Banate Hain, showing how co-making preserves voice while renewing skills. The conversation asks which eco-social literacies—situated inquiry, cultural stewardship, and ethical collaboration—students need to move ideas into practice.

How has your experience teaching at institutions like NID and IDC shaped your views on the evolution of design education in India, particularly in addressing social and environmental issues?

When I joined NID in 1980, after completing my undergraduate studies at the Faculty of Fine Arts, M. S. University, Baroda, I was introduced to the idea of social responsibility in design. In Fine Arts, the emphasis had been on self-reflection and personal artistic pursuit, whereas at NID, the focus shifted toward social issues and the responsibility of communicating meaningfully with communities and society at large. This was not abstract theory; it was grounded in real projects that addressed actual needs in areas such as healthcare and adult education.

I vividly recall working on an animated short film on adult literacy, which required us to interview people who had never attended school. I chose to engage with women beedi workers, and what I learned from them has stayed with me ever since. When I suggested that education could improve their earnings, they challenged this assumption, pointing out that many educated individuals remained unemployed while they themselves earned more consistently. Their motivation for learning was rooted not in economic advancement but in dignity—the ability to sign their own names instead of using thumbprints, and to read and write letters to their children. This powerful lesson taught me that design cannot rely on assumptions; it must begin with people’s lived realities. That understanding became a cornerstone of my practice and later shaped my approach to design education, influencing curriculum development at both NID and, later, at IDC.

You've been involved in both traditional design education and new media programs. How do you see the role of traditional art forms and new technologies in fostering "eco-social literacies"?

New technologies are firmly rooted in the foundations of traditional design education. While they represent a distinct evolution, they remain inseparable from the principles that shaped earlier pedagogies. Traditional design education was largely specialization-driven, emphasizing expertise within a single discipline. In contrast, contemporary programs—such as New Media and transmedia—are increasingly guided by purpose, focusing on intent and impact rather than being confined to domain-specific skills.

Both traditional and contemporary approaches engage with eco-social literacies, often through storytelling and, more recently, immersive technologies. Traditional methods may sometimes appear more passive or less participatory, yet they remain powerful in their reach and effectiveness, often addressing much broader audiences. New Media, by contrast, creates immersive, experiential formats that resonate strongly with particular groups, though they have yet to achieve the same degree of pervasiveness. In my view, both are necessary, and each contributes something valuable to education and communication.

A key distinction between the two lies in their relationship to materials. Traditional design education emphasizes direct engagement with materiality—understanding the properties, limitations, and possibilities of physical media through hands-on exploration. This material-centered approach fosters not only technical skill but also a deeper sensitivity to context and process. New media technologies, however, remain primarily within digital environments, with limited interaction beyond the screen. While AR, VR, and AI can simulate touch and texture, these are still representations rather than true encounters with materiality. This difference highlights a fundamental divide between practices grounded in the tangible and those situated in the virtual. At the same time, it opens up new possibilities for dialogue between the physical and the digital, pointing toward future pedagogies that integrate both traditions.

Based on your experience, what are the most critical mindsets or capacities that design students need to develop to navigate today’s complex socio-cultural and ecological challenges?

Design students today need more than technical skills; they need mindsets that prepare them for complex socio-cultural and ecological realities. Empathy and social responsibility are central, allowing them to design with and not just for communities. Systems thinking helps them understand how ecological, cultural, and economic factors are interconnected. Equally, material sensitivity builds an ethical awareness of sustainability, whether in physical or digital realms. Alongside this, adaptability and openness to emerging technologies such as AR, VR, and AI must be balanced with critical reflection to question dominant narratives and imagine alternative futures. Storytelling and collaboration complete the picture, enabling students to communicate effectively across audiences and work across diciplines. Together, these capacities create designers who can respond to urgent challenges with creativity, responsibility, and resilience.

On Practice and the Designer's Role

You blend animation and ethnography to tell stories. How does this interdisciplinary approach help you address complex issues like communal well-being and cultural preservation?

Blending animation and ethnography creates a powerful interdisciplinary approach to storytelling, one that can illuminate complex issues of communal well-being and cultural preservation in ways that other forms of representation cannot. Ethnography brings depth through lived experiences, oral histories, and cultural practices, while animation provides a medium that can translate these insights into visual narratives that are both accessible and emotionally resonant.

Animation has the ability to transcend language and literacy barriers, enabling stories to reach diverse audiences, including those who may not connect with conventional academic or textual forms of ethnography. Through symbolic imagery, metaphor, and visual abstraction, animation can capture aspects of cultural knowledge, memory, and emotion that might otherwise remain invisible or difficult to communicate. For example, rituals, oral traditions, or ecological wisdom can be animated in ways that preserve their essence while making them accessible to younger generations and global audiences.

When combined with ethnographic sensitivity, this approach avoids the pitfalls of exoticization or oversimplification. Instead, it fosters respect for community voices, ensuring that stories are co-created or at least deeply informed by the people whose lives are being represented. In doing so, animation becomes more than a creative tool—it becomes a bridge for dialogue between communities, scholars, and the wider public.

In terms of communal well-being, such storytelling can validate identities, strengthen intergenerational connections, and foster empathy across cultural divides. Communities often find empowerment in seeing their experiences represented with dignity and creativity, which can contribute to healing, resilience, and social cohesion. For cultural preservation, animation offers a durable, shareable form of knowledge transmission. It allows cultural practices that are fragile, endangered, or changing under modern pressures to be documented, celebrated, and kept alive in ways that are both respectful and engaging. I recall a striking moment during a festival screening of Tanko Bole Chhe (The Stitches Speak). After the film, a viewer remarked, “Oh, that’s such a wonderful story.” One of the artists from Kutch immediately responded, “It’s not a story—it’s our history.” That exchange stayed with me, because it underscored how animation, when combined with ethnographic practice, does not simply tell stories in the abstract. For the communities involved, it becomes a way of narrating lived histories, preserving memory, and affirming identity.

In your film collaborations with indigenous communities, like with the Bhil artist Sher Singh, how did you navigate the role of designer versus facilitator?

When I look back at the making of Hum Chitra Banate Hain (We Make Images), I realize that both Sher Singh and I played many roles, even if neither of us consciously defined them. The collaboration itself was simple: Sher Singh painted the images, and my team animated them. The story unfolded organically through conversations with him, his family, and other Bhil artists. He had no interest in learning animation, just as I did not wish to imitate his paintings. Instead, we both stayed true to our strengths, while remaining open to each other’s insights.

Sher Singh responded to the script and storyboard in his own unique way, often offering suggestions that shifted the direction of the film. I sometimes asked him to paint elements he had not attempted before, and he rose to the challenge with curiosity. One memorable instance was when we were discussing the title of the film. Since the story centered on a rooster who survives to tell the tale of water conservation, I suggested The Tale of a Rooster. To my surprise, Sher Singh proposed The Tale of a Peacock. I reminded him that there was no peacock in the story. He replied, quite simply, that he would paint one, and I could place it in the film.

When I asked why a peacock, his answer startled me: “Because he is beautiful.” For me, this posed a dilemma. I was attached to the causal logic of the narrative, while Sher Singh was responding through a symbolic lens. I suggested the compromise title We Make Images, which satisfied us both. When I pressed him further on why he resisted The Tale of a Rooster, he explained that the rooster is a sacrificial bird. His reasoning revealed a depth of meaning that I had overlooked, bound as I was by narrative causality.

This exchange became an eye-opener. It showed me how collaboration thrives not in imposing one’s own framework but in mutual respect that bridges differences. The outcome—a title that carried more power and inclusivity—was something neither of us could have arrived at alone. In this process, I did not see myself as a facilitator or even as a designer. I was, above all, a collaborator.

Your work often involves "bringing together animation and ethnography." Can you share a specific example of how this process helped uncover or address a socio-cultural issue that a more conventional design approach might have missed?

I think the above could also serve as an example.

On Broader Reflections and Future Outlook

Your doctoral research on the Kaavad storytelling tradition focused on an art form that is a "portable pilgrimage." What lessons can we draw from this tradition about a "sustainable" practice that is both socially and environmentally regenerative?

Today, the Kaavad may be perceived as an obsolescent artifact belonging to an obsolescent community, poised on the brink of disappearance. Its fate seems sealed in the conventional options of preservation: it can be museumized, transformed into a tourist spectacle, or commodified for niche markets. Yet, all these options risk marginalizing the Kaavad further, reducing it from a living tradition into a subsistence activity or, worse, a decorative relic.

However, if we extend Bruno Latour’s idea that design is reinvention, a different possibility emerges. Design, in this sense, is not repair, nor is it a nostalgic act of preservation. It is both remembering and creating—a process of recoding an artifact by placing it into new contexts, whether in media, education, or other domains of practice. The Kaavad, understood not only as a physical object but as a “concept box,” invites designers to adopt a new ethics of memory. Here, design does not simply replicate or aestheticize tradition but attempts to sustain the community for whom the artifact carries meaning.

My illustrated book Home was conceived in this spirit. Borrowing the structure of the Kaavad, it adds to the old creation myth by offering new narratives of survival. In doing so, Home creates a space where orality is reimagined as part of children’s literature—where words and images do not compete but share a symbiotic relationship. The Kaavad thus becomes more than a case of cultural preservation; it becomes a pedagogical tool, an ethical framework, and a reminder that design is at its most powerful when it sustains memory while opening pathways for renewal.

You've seen the design landscape change over many decades. Looking ahead, what do you see as the most pressing "unknown" challenge that eco-social practitioners will face, and how can they prepare for it?

The most urgent challenge for eco-social practitioners is the unknown itself—the unpredictable disruptions born from the entanglement of climate, technology, politics, and culture. The unknown cannot be forecast or fully prepared for; it unsettles every model we build. Preparation, then, is not about prediction but about cultivating responsiveness. Practitioners must design with resilience, drawing on diverse knowledge systems, building networks of care, and keeping practices open to reinvention. Survival depends on sustaining multiple ways of knowing and being, rather than collapsing them into one. To meet the unknown, eco-social practitioners must embrace humility, imagination, and accountability. The task is not to master uncertainty but to turn it into a ground for collaboration and renewal—where design, memory, and community come together as tools for collective survival.

How do you believe your work with traditional artisans and craft communities bridges the gap between design theory and its practical application in achieving eco-social transformation?

I cannot say with certainty that my work bridges the gap between design theory and practice in achieving eco-social transformation—such a claim would be too ambitious. What I can say is that my practice is an attempt to blur boundaries between formal design, which often carries an individualistic focus, and community knowledge, which thrives on collaboration.

For me, the key lies in learning how to work together—with people, with traditions, with environments, and with systems that are not always visible. Any real transformation requires this collective effort. My work, therefore, is less about offering solutions and more about creating opportunities for collaboration—spaces where different voices and knowledges can interact. In that process, design itself is redefined, not as a tool of mastery, but as a shared practice of listening, remembering, and co-creating.

Looking back at your long experience, what is the ultimate purpose or "north star" that guides your design approach and efforts for eco-social transformation?

I look forward to a world where collaboration and mutual respect blur the divides between those who are formally trained and those whose knowledge is tacit, intuitive, or embodied. The long-standing hierarchy that separates art, design, and craft has often diminished the dignity and value of practices rooted in tradition. Yet, each carries its own wisdom and deserves recognition within a shared ecology of making.

As Tim Ingold suggests, making and knowing are inseparable; knowledge does not only reside in the head but also in the hands and in practice. Similarly, Bruno Latour reminds us that design is not simply about producing novelty but about re-coding, remembering, and transforming practices in new contexts. From this perspective, collaboration becomes an ethical act: a way to sustain communities, affirm traditions, and generate new possibilities for eco-social transformation.

In this sense, design cannot remain a highly individualistic activity—it must learn to engage with all systems of knowledge, formal and informal, to bring about meaningful change.