In recent years, design has increasingly been called upon to take a stand: socially, politically, and structurally. But what does that mean in practice – for those who teach design, for students, and for the places where design intervenes? In this in-depth conversation, Jesko Fezer reflects on design as a situated, political, and often ambivalent practice. Drawing from his teaching, long-standing design collaborations, and real-world project work, he discusses partisanship, the role of local engagement, and the limits of design’s transformative promise.

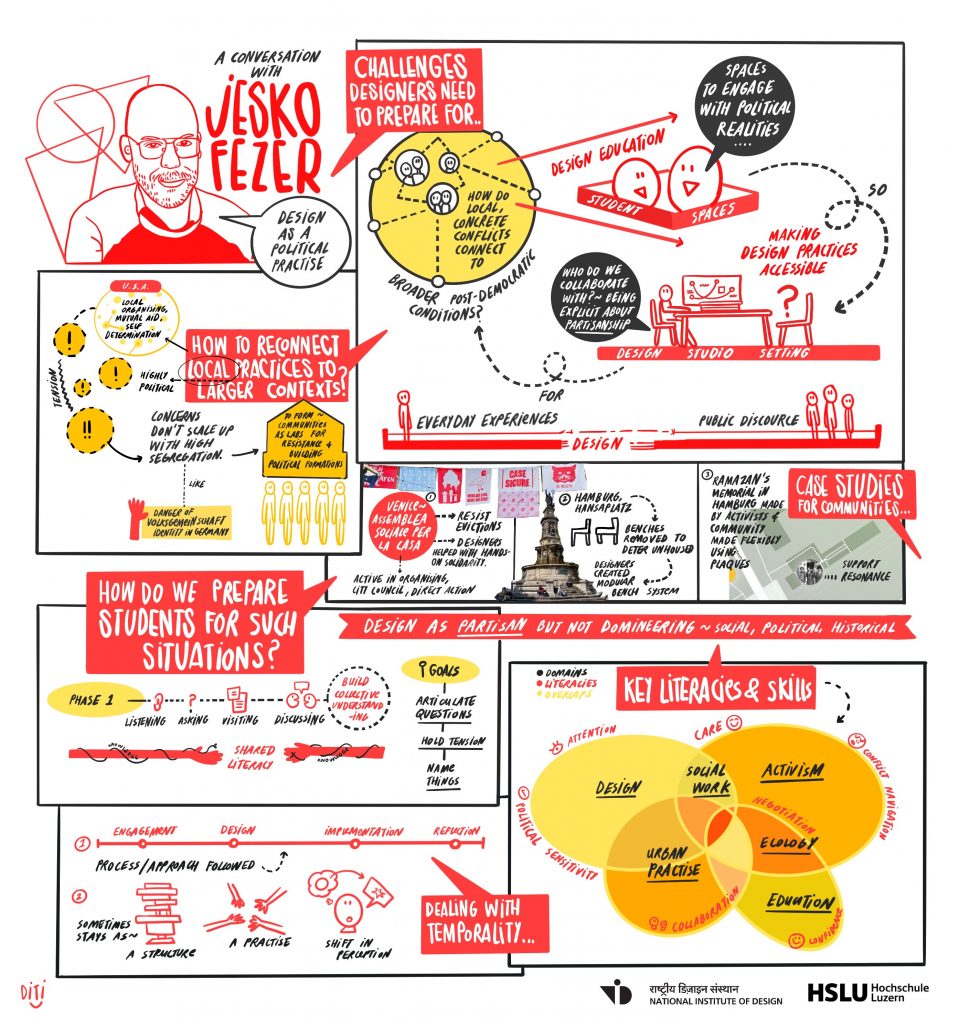

When you think about your students, your studio – what are the major challenges you feel designers need to prepare for today?

Over the past few years, a perspective has emerged in our work that wasn’t fully clear to me at the beginning. It wasn’t the result of a strategic plan, but something that took shape through doing things together. I’d say it’s increasingly about connecting short-term, local design interventions with something that resembles social groundwork – all in the context, or perhaps in the wake, of a massive right-wing shift in politics. I’m interested in how very concrete, local conflicts – the kinds we encounter in neighborhoods – relate to this broader post-democratic condition. Can design education open up spaces that allow students to engage with these realities? Where are the political, social, or activist spaces that are grounded in everyday life – and that derive their legitimacy and urgency from those contexts?

In our studio, we often talk about making design practices accessible – even popular, in the best sense. This means being explicit about partisanship: Who do we support? Who are we working with? Who gets to speak – and who doesn’t? That’s not just about taking a position, but about reactivating democratic conflict through design. And I believe this can only happen if we take local, situated design seriously – not as a reduction, but as a mode of practice in which conflicts can be processed, expanded, connected to others. Design can help us bridge everyday experiences and public discourse – not by representing them, but by intervening. If you follow that logic, you end up asking questions about scale and structure: How can political questions emerge from local forms of engagement? And how can major social and ecological conflicts be addressed at the neighborhood level – without simplifying them, but also without overwhelming everyone involved?

I often notice how deeply political local discourses can be – sometimes even more than in formal politics. But how can we reconnect those local practices to larger societal contexts?

That’s exactly the challenge. There’s a strong tradition of community-based practice in the U.S., and a lot of what we discuss in Europe comes from there – local organizing, self-determination, mutual aid. But there’s also a sharp divide: Many of these communities are highly segregated, and their concerns often don’t translate into broader political discourse. That’s the dilemma. Community can position itself as a counter-model to society – and in Germany, we know how dangerous that can be. The concept of the Volksgemeinschaft replaced the idea of an open society with a homogenized, exclusive identity. That’s a conflict we haven’t resolved: society tries to regulate or dissolve communities, while communities often resist integration into societal structures. Still, I think there’s a productive space in that tension. Not a comfortable one, but a meaningful one. The key question is: How can small-scale, localized problems be connected to large-scale social concerns? And how can larger political discourses take local realities seriously, not just instrumentalize or ignore them? Community-based practice shouldn’t be understood as withdrawal, but as part of a larger circulation of political work. These spaces can act as laboratories – not only for resistance, but for building more substantial political formations.

Can you share some examples where this perspective becomes tangible?

Sure. One example is a project we did in Venice with Assemblea Sociale per la Casa. They occupy vacant apartments and support people facing eviction. They already do political work – organizing in neighborhoods, speaking at city council meetings, and engaging in direct action. We didn’t go there to make a big design gesture. We helped them with basic things: building a crib, repairing shutters, putting up shelves. It was a form of solidarity – practical, hands-on. They were already formulating the political questions. Our role was to contribute on a very concrete level.

Another project was in Hamburg, at Hansaplatz – a heavily surveilled square where all the benches had been removed to deter unhoused people. The area was still used by people with diverse needs, but also deeply stigmatized. Local residents wanted to reclaim the space, not out of romanticism, but because they wanted to sit there, play chess, and talk. We developed a system where people could store bench modules at home or in shops and bring them out when needed. It wasn’t just functional – it was symbolic. A small workaround that allowed for co-existence, and a critique of how public space is governed.

And then there’s the Ramazan Avcı memorial in Hamburg. He was murdered by neo-Nazis in 1985, and there was no proper site of remembrance at the place of the crime. A community initiative, including members of his family, pushed for a public memorial. We worked with them to create a growing, flexible format – a plaque with a banner that could be updated to include the names of other victims of racist violence. Our task wasn’t to define the political narrative, but to support the space in which it could resonate. To make visible what was already being articulated.

These kinds of projects illustrate how design can be partisan without being domineering. The challenge is to hold together different readings of a situation – social, political, historical – and still remain capable of action.

How do you prepare students for these kinds of situations?

We work with a structure that slows the process down at the beginning. The first phase is about getting to know people and contexts – listening, asking, visiting, discussing. Only after that do we start developing ideas. This helps students recognize what they’ve heard – and what they may have missed. It gives space to see how others perceive the situation. From there, we build collective understanding without rushing into solutions.

Alongside that, I suggest readings and host a group seminar that runs parallel to the projects. We reflect on issues that came up but weren’t fully addressed in the projects – or we dive into concepts that help articulate what’s going on. It’s not a traditional lecture. It’s more like building shared literacy over time. The goal isn’t mastery. It’s about becoming articulate – being able to ask better questions, to hold tension, to be able to name things. In the end, the work shouldn’t be just personal experience, but part of a shared learning process.

I assume your students won’t all go on to do community-based work. What kind of literacies do you try to cultivate, and how do you think they translate into other contexts?

That’s true. And I’m not training students for a single profession. At art schools, that’s rarely the case. What I hope to provide is a space where they can try things, reflect, and make decisions. That includes attention, care, political sensitivity – but also organizational skills and the ability to collaborate. It’s basic stuff, really: How do you develop a project? How do you navigate conflicting needs? How do you bring something to a close, even when the situation is messy? Those skills apply across fields – whether someone works in visual design, spatial practice, education, or urban contexts. But I’m also interested in less-defined spaces of practice: where design overlaps with social work, activism, pedagogy, or ecology. For that, you need confidence in your own judgment – and the language to negotiate.

One semester is not a lot of time for such deep engagement. How do you deal with that temporality – and the responsibility that comes with it?

You are absolutely right. It is almost impossible to engage with real-world issues and partners or clients from non-academic contexts within the framework of one or even two semesters. Many of our projects take 2-3 years or are even endless if a kind of long-term cooperation between the studio and an initiative or individual has been established. Our privilege (and problem) at the HFBK is that we have classes where students can work with a professor as a team throughout their entire studies, if they wish. So, we have enough time to listen and observe, develop something together, realize it if possible, and finally reflect, document, and hand it over. Sometimes another student group continues the work. Sometimes the project ends, but something remains – a structure, a practice, a shift in perception. That can be enough.

Do you assign topics or locations?

No, I avoid that on purpose. Not because I don’t have ideas, but because I believe topics should emerge from the process. Students choose the sites and partners, often with my support. I can suggest contacts or questions, but I try not to steer too much. It’s part of the learning: figuring out what matters to you, where you want to get involved – even when nothing works out. That’s a valuable experience, too. Good teaching, I think, supports open-ended processes without making them vague. It helps hold tensions without resolving them prematurely. And it makes responsibility possible – without leaving students alone with it.

Looking back – at the teaching, the projects, the challenges: What is it ultimately about for you?

I don’t think design can solve social problems – not in a technical sense. What interests me is how we can entangle ourselves in these problems without becoming arrogant. How we can be part of something larger – and still stay able to act. That means: don’t wait for the perfect answer. Start somewhere. Start small. Navigate ambiguity. But also: don’t stop there. Keep asking: What does this mean – politically, structurally, historically?

Maybe, in the end, it’s about understanding design not as an instrument of control, but as a relational practice. A way of being in contact with the world. And if something meaningful arises from that – something useful to others, not just yourself – then that’s already a lot.

Jesko Fezer is a designer and educator. In various collaborations, he engages practically and theoretically with the socio-political relevance of design. In cooperation with ifau (Institute for Applied Urban Studies), he realizes architecture projects; he is co-founder of the Berlin bookstore Pro qm and part of the exhibition design collective Kooperative für Darstellungspolitik. He co-edits the Bauwelt Fundamente series and Studienhefte für problemorientiertes Design. Jesko Fezer is Professor for Experimental Design at the Hamburg University of Fine Arts, where he has been running the student-led Public Design Support program since 2011. His latest publication is Umstrittene Methoden (Adocs 2022), on architectural discourses of politicization, participation, and scientification in the 1960s.