Valerio Rocco Orlando is an Italian Artist, and holds a PhD in Engineering-based Architecture and Urban Planning from Sapienza Università di Roma. Through practices ranging from workshops to video installations, he conceives art as a process of mutual knowledge and understanding. The core of his work is the exploration of osmosis among institutions, museums, academia, and the social sphere.

His works are held in public and private collections, including: A. M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, Havana; Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon; La Galleria Nazionale, Rome; MACRO, Rome; MAGA, Gallarate; Mart, Rovereto; Museo del Novecento, Milan; MUSMA, Matera; Nomas Foundation, Rome; VAF Stiftung, Frankfurt am Main; Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese.

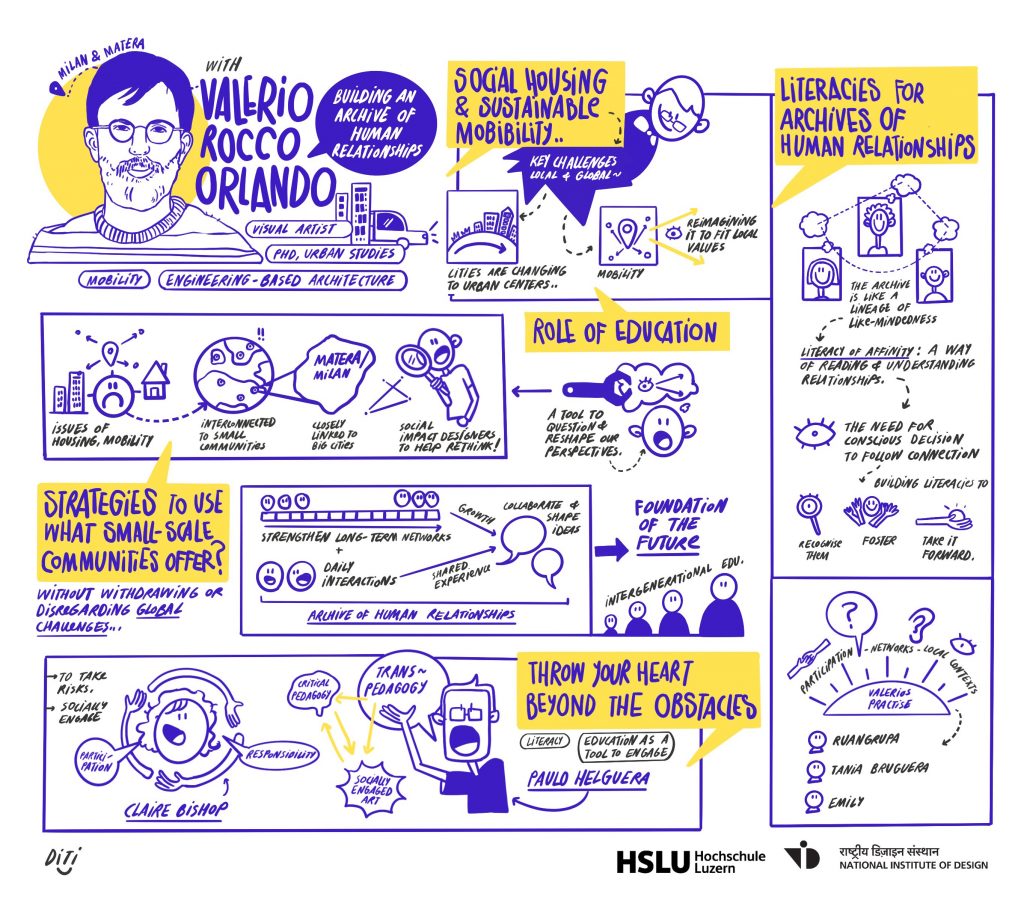

Social housing and sustainable mobility as imperatives of urbanity

Valerio Rocco Orlando lives in Milan and Matera. He recently finished his PhD at the Sapienza University in Rome and currently works in at Scuola dei Sassi, Matera. It is in this context that challenges around social housing and sustainable mobility emerge as the important imperatives that engage artists and eco-social designers alike.

Valerio: In the last three years, during my PhD research at Sapienza, University of Rome, I’ve had the opportunity to explore and better understand the issues surrounding social housing. It remains a major challenge—not just in Italy, but globally—especially as cities are changing rapidly, with increasing private investment in urban centers and large metropolitan areas. Mobility is something we need to talk about, especially considering how our generation is used to travel. I’ve spent most of my life moving between places—Cuba, India, South Korea, Iceland, Palestine, Morocco, Egypt—working with different communities. But now, I feel the need to focus differently, I want to work on a more local scale. We have ourselves to start from reimagining mobility in a way that aligns with our values and aims in our work.

»But now, I feel the need to focus differently, I want to work on a more local scale. We have ourselves to start from reimagining mobility in a way that aligns with our values and aims in our work.«

You are working on the topic of education – from an artist's perspective. What is the role of education in the context of the imperatives of social housing and mobility?

If we want to rethink our cities and the way we live, education can be a tool to question and reshape our perspectives. These issues—housing, mobility, urban life—are all tied to the idea of small-scale community interventions. Small-scale communities, however, like Matera or even Lucerne, are closely linked to the dynamics of major cities like Basel, Zurich, or Milan and we have to understand these dynamics. At the same time, smaller cities and communities can be more independent in terms of policymaking, and citizen-driven decisions. As artists and practitioners engaged in social practice, we have an opportunity to make a real impact—but only if we work together. In the past, I thought that to work as an artist, I had to be in New York, London, or Paris. But now, I no longer believe that’s where change happens. Instead, small-scale communities offer a space to rethink social housing, sustainable mobility, and education in a more interconnected way.

Building an Archive of Human Relationships

If we aim at using the opportunities small scale communities offer, what kind of strategies can support us? And how can we make sure, that we do not withdraw «from the world» and disregard the more global challenges?

I believe we need to strengthen our networks on two levels: long-term relationships and everyday interactions. Working as an artist or as an educator, both of us are deeply engaged with our small-scale communities on a daily basis. At the same time, we remain committed to our broader, global networks through regular discussions and exchanges. This ongoing dialogue allows us to collaborate and shape new ideas—building up key concepts that define our work. I would say, we build an Archive of Human Relationships. An archive is often seen as something that preserves the past, but I see it differently. For me, an archive is a layering of relationships—a structure built from shared experiences, constantly growing and shaping the future. To build this archive is my current aim that connects people and ideas in my projects. How do I imagine this? For example, when we first met in Milan in 2016, we were part of a group of students and professors meeting together for something as simple as a conversation. This created a space that enabled another layer: We started a dialogue, built trust, and created a long-term connection. That moment became the first part of our shared archive of human relationships. But this archive isn’t just about looking back—it’s a foundation for the future. It allows us to understand how knowledge and care can be shared across generations, shaping new collaborations and learning processes. It’s about building something that continues to evolve. I believe these archives of human relationships can only exist if we share trust and recognize the importance of reciprocity. However, reciprocity is not necessarily horizontal. Even when we share common ground, we are not the same—we come from different backgrounds, different generations, and different life experiences. This is especially relevant when we talk about intergenerational education. That’s why I believe in what is called asymmetrical reciprocity: an understanding that, while we are all on different paths, we can still collaborate in finding ways forward together, even if we may be on different missions.

Literacy of affinities

What literacy would we need if we want to build our archives of human relationships?

The archive is like a family tree, but not one based on bloodlines. Instead, it’s about affinities, about how minds align rather than just lineage. This kind of connection isn’t predetermined; it emerges through shared experiences, through learning together. And if we translate this into education, we might call it a literacy of affinity—a way of reading and understanding relationships as they form.

Let me get back to the example when we first met: The group of students and professors formed a kind of system of relations, even if it’s implicit. Learning to read that system - recognizing who you naturally connect with, understanding how relationships emerge - is not only an intuitive process. But it also requires a conscious decision to follow that connection and see where it leads. So maybe this archive is not just about preserving relationships but about developing the literacy to recognize them, to foster them, and to carry them forward.

Donna Haraway was also talking about this concept of creating relationships: “Making kin, not babies”. That’s why I see my practice also as connected to artists like ruangrupa, Tania Bruguera, and Emily Jacir, who all work with participation, networks, and local contexts. Socially engaged art is not just about making something visible; it’s about working with people, building relationships, and creating spaces where new ideas can emerge. It’s not like learning how to paint or sculpt—it’s more about observing, listening, and understanding what role we can take as artists, students, or designers in a specific community.

The literacy to “throw your heart beyond the obstacle” – or “Gettare il cuore oltre l'ostacolo”.

Being an artist working with and through social relations, you are yourself the material and the tool at the same time– you have to be daring and go out in the world and produce a position. This is something that does not always come naturally to design students. To make engagement happen, one of the tools you «use» is education – what does this mean in practice?

Pablo Helguera talks about transpedagogy, this idea of combining socially engaged art with critical pedagogy, and I think that’s exactly where my work fits in. It’s about rethinking education through art, not in a theoretical way only, but as a real practice—how we work together, how we share knowledge, how we make things happen. Claire Bishop wrote a lot about participation in art, and what I find most interesting is this question of responsibility: What does it mean to engage with a community? What does it mean to create something together? It really means to be able to “mettersi in gioco” and about “gettare il cuore oltre l’ostacolo”– meaning: take a risk, put yourself into the game and do it wholeheartedly!

We must be courageous. It’s about realizing you’re not alone in that space—whether it’s eco-social design, socially engaged art, or something else. Small-scale communities form in classrooms, in cities like Matera or Lucerne, among students, alumni, and professors: Long-term relationships, all contributing to a shared archive of human relations.