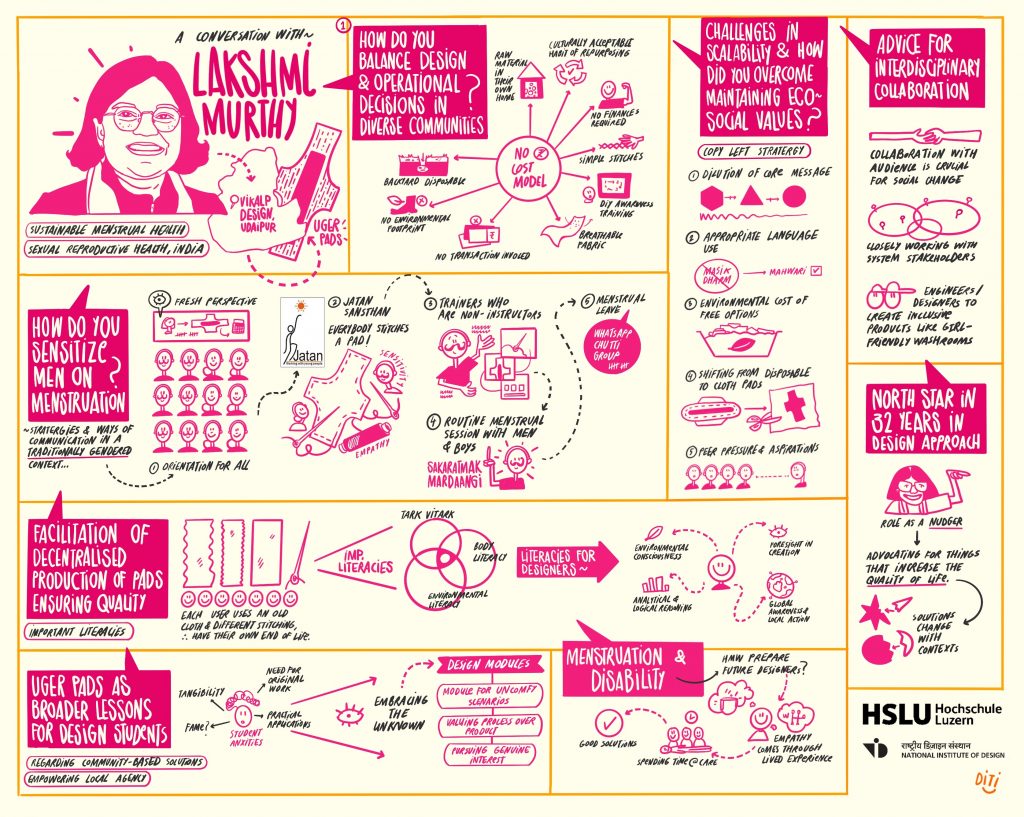

Lakshmi Murthy is a designer, researcher, and educator whose work bridges communication design, public health, and social innovation. A graduate of NID Ahmedabad (1986) and founder of Vikalp Design in Udaipur, she has spent over 35 years working at the intersection of reproductive health, gender, and sustainability. Her doctoral research at IIT Bombay explored the sustainability of menstruation management, complementing decades of practice-based engagement in rural and urban communities.

Central to her approach is the conviction that communication design can drive social transformation. Through Uger Pads, a social enterprise producing reusable cloth pads, Murthy and her team integrate environmental awareness, affordability, and gender inclusivity. They have reached tens of thousands of women, adolescents, and men through training and advocacy — reshaping menstrual health as both a design and societal challenge.

The following conversation explores Lakshmi Murthy’s reflections on eco-social design, participatory literacies, and the pedagogical implications of her work.

On Impact

Uger Pads emphasize both ecological sustainability and social impact. How do you balance these two aspects in your design and operational decisions, especially when considering affordability and accessibility for diverse communities?

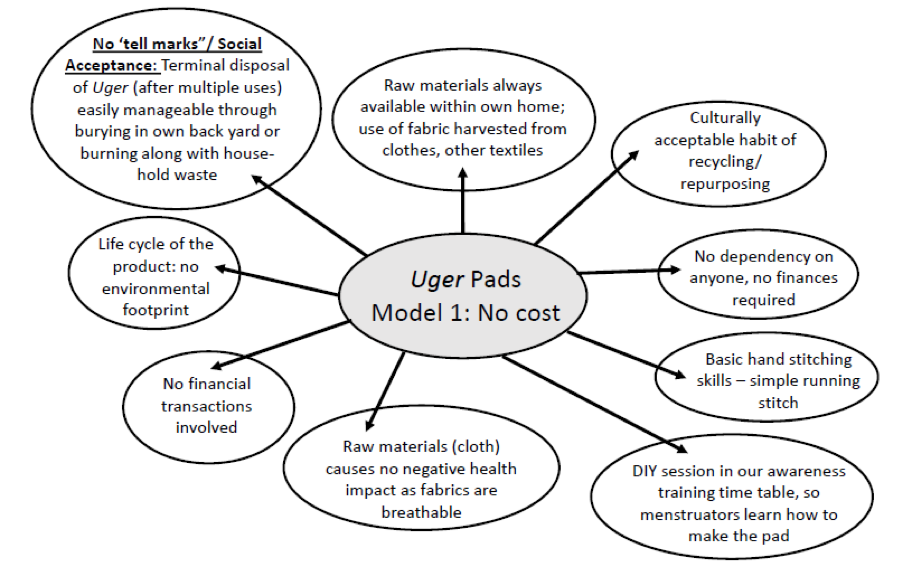

Our No-Cost Model provides affordability/accessibility (economic, social factor). It is also sustainable from the point of view of the environment and health. The figure below consolidates all these aspects.

Your work with Uger Pads involves sensitizing men about menstruation. What design strategies or communication approaches have you found most effective in engaging men in this traditionally gendered conversation? How do these strategies contribute to broader eco-social transformation?

In the first instance, sensitization begins at our office itself during the orientation session for new joiners. Whether a non-menstruator or a menstruator, all receive a crash session in menstrual health. Menstruation, often engulfed by misconceptions, superstition, and a lack of scientific knowledge, gets a fresh perspective as a biological phenomenon that concerns society as a whole, not just menstruators.

All new joiners at Jatan Sansthan stitch a cloth pad. This activity serves as a session in empathy and sensitivity. This is the first step toward transformation, "breaking the silence" and "making that move toward open conversation," initially among office colleagues, then at home with family, and subsequently within the community.

We have menstrual health trainers who are non-menstruators. The strong message conveyed is that menstrual health concerns us all. Therefore, it is not necessary for a menstruator to be a trainer; everyone can be a trainer for menstrual health.

We have routine menstrual health sessions with young boys and men as part of our "positive masculinity / sakaraatmak mardaangi" sessions. These sessions include games and activities that sensitize participants to issues around gender.

Another strategy is the granting of Menstrual Leave (ML) to those who require it. (While it is not truly a strategy and ML is often misused, hence hugely debated, this is how the leave works.) We have a "chutti" (leave) WhatsApp group. This group informs colleagues when anyone takes leave—Casual Leave (CL), Privilege Leave (PL), or Sick Leave—which is especially useful for those with field-level work. Menstruators in our office have to declare they are on ML in the "chutti" group. This open declaration is encouraged as an act of breaking silence ("chupee todo"), and this sensitizes non-menstruators in the process.

You've scaled your intervention to reach tens of thousands of women, adolescents, and men. What were the key design and communication challenges you faced in achieving this scale, and how did you overcome them while maintaining the core eco-social values of your product?

The scale-up of our initiatives has been possible due to our "Copy Left" strategy. This approach allows other groups to advance menstrual health by utilizing and adhering to our core training modules and teaching-learning materials.

Challenges

What are some of the challenges you are grappling with?

While our "Copy Left" strategy encourages adaptation, groups often modify sessions or materials in ways they want. This sometimes leads to the original messages, concepts, or meanings becoming misconstrued or diluted. However, we see this "trickle-down" dilution as preferable to a complete lack of menstrual health communication and conversation.

Another significant challenge lies in the consistent use of appropriate language. For instance, we discourage the term "masik dharm" due to its religious connotations. We prefer groups use "mahwari" to completely dissociate menstruation from religion. Given that "masik dharm" has been used for a long time, changing this ingrained terminology will take time.

Moreover, menstrual management options available at no cost, such as disposable sanitary napkins from Anganwadi centers, are often non-biodegradable. This presents a significant environmental cost. A large segment of the rural adolescent population has grown up using free disposable pads. Converting this group to cloth pads, which they've never used before, is challenging. However, in very remote locations where government pad supplies are non-existent, cloth remains a crucial and relevant option.

But the perception that market-based menstrual products are superior to homemade ones remains strong among young people. Homemade options are often seen as old-fashioned and not trendy, while disposable pads are viewed as modern and aspirational.

The "no-cost" model using old garments is a powerful example of resourcefulness and community engagement. From a design perspective, how do you facilitate this decentralized production while ensuring quality and user acceptance? What "literacies" are important for users in this model?

The diagram above addresses some aspects of decentralized production and user acceptance. The question of quality is less relevant in the no-cost model because old cloth is used. Consequently, each user will have a different type of fabric with varying absorbency levels and different degrees of wear and tear, meaning previously used fabric will have its own "end-of-life" process. Moreover, the stitching skills of users vary, so uniformity can never be achieved. Of course, in the pads stitched from new fabric, quality is maintained at the production center.

In terms of literacy, I can think of several perspectives. With Environmental Literacy, for example, we could describe the understanding that every single action or decision we make can either help or harm our surroundings, depending on the choices we make. The convenience of the government's free pad supply often just overrides all those other environmental concerns, which is a real challenge. Body Literacy would describe having a good grasp of our body parts and what they do. It really helps us understand how everything's connected, why good health is so crucial, and how any positive health action can lead to better menstrual health. Then I would add "Tark-Vitark" (Hindi for Analyzing after Examining), which is about being open to new ideas and really thinking logically. For example, there's this really strong belief in some communities that you can get pregnant while menstruating, so young people are often told to stay away from their partners during that time. "Tark-Vitark" is about having the ability to look at that practice scientifically and logically.

Connecting to Design Education & Literacies

Your academic background in sustainability of menstruation management at IIT Bombay, combined with your practical work, offers a unique perspective. What "eco-social literacies" do you believe are most critical for design students today, particularly those interested in health, social impact, and sustainable product development?

In addition to the ones described above, I would add several:

Environmental Consciousness: Understanding our impact on the planet is crucial.

Foresight in Creation: It's about being able to predict the potential long-term consequences of the work we create. Think about Bisleri bottles or Tetra Paks—they were great inventions, but their devastating aftermath is now staring us in the face.

Analytical and Logical Thinking: This involves building the capacity to challenge societal norms, but also to recognize and accept older systems that might still be relevant today.

Global Awareness and Local Action: This is about being aware of occurrences and trends worldwide. The old slogan, "think globally, act locally," still holds true. Rural or urban, young people are constantly bombarded with information via social media algorithms. The ability to critically navigate social media and cultivate mindful consumption of digital information is vital. Learning to disengage from constant comparisons and the incessant "wanting for things" can significantly improve one's mental well-being.

How do you see your work with Uger Pads, particularly its focus on breaking silence and local product creation, translating into broader lessons for design education regarding community-based solutions and empowering local agency?

Students often grapple with anxieties like, "My creation has to be original; I need to make a tangible thing. My solution must have a practical application otherwise, what's the point? Working on solutions for the poor won't catapult me into fame," and so on. Learning about design is a lifelong journey, and within the design curriculum, some broader philosophies and lessons can be incorporated:

Embracing the Unknown: Students should embark on or step into unknown and uncomfortable spaces. A typical design student isn't always comfortable going into areas like communities living under a flyover, those on the edge of railway tracks, or in domestic dwellings on construction sites. A module focused on this should be made compulsory, taking an ethnographic approach. The goal wouldn't be to create design solutions but simply to engage in deep observation and reflection on these spaces. While environmental perception touches on this to some extent, a deeper dive would be incredibly beneficial. For example, shadowing one or two families over a week could help students begin to understand their lives better. This could reveal seemingly simple things, like the purchase of provisions: buying food materials in smaller quantities due to limited storage space, or a family living under a flyover buying only enough for two days. Students would return with a clearer understanding of how things work in a non-profit space after such an immersive experience.

Valuing the Process over the Product: Learning and experimenting as a student has more value than focusing on a tangible end item. It's perfectly okay if a solution can't be implemented; the processes of a design journey are far more important.

Pursuing Genuine Interest: Students should focus on what truly interests them, rather than expecting or wanting accolades.

You aim to initiate new work on menstruation and disability, a topic with limited attention. What specific design considerations and research approaches do you anticipate will be crucial for addressing this challenge, and how would you prepare future designers for such specialized and sensitive areas?

Empathy, comes through lived experience. Spending many hours of quality time with families who are caring for their disabled family member, spending time at care home… will lead to more accurate reflections and hence practical/good solutions .

Reflecting on your journey, what role has interdisciplinary collaboration played in the success of Uger Pads? What advice would you give to design students about cultivating the ability to collaborate effectively across different fields (e.g., public health, social work, engineering)?

Collaboration with your target audience is absolutely crucial for social change. In Uger's case, this means working closely with adolescents, parents, teachers, and village leaders like the Sarpanch and other local functionaries. Relying on just one factor for social change won't work; it requires sensitization at multiple levels. For instance, government engineers need to be sensitized on how to design "girl-friendly" bathrooms, ensuring enough privacy with walls high enough to prevent peeping.

Applying this generally to students, it's vital to constantly converse and reflect, maintaining awareness of their surroundings. They need to cultivate patience as they gather diverse perspectives on the subjects they're working on. And, seriously, peel your eyes away from social media!

Broader Reflections

Looking back at your 32 years in reproductive health and your work with Uger Pads, what is the ultimate purpose or "north star" that guides your design approach and efforts for eco-social transformation?

Coming from a place of privilege, I deeply understand how circumstances shape individuals and how easily one can feel cornered by them. In my own life, I've been fortunate to have inspiring people who supported my aspirations and nudged me in beneficial directions, rather than pulling me down.

I see my role as that of a "nudger" – advocating for things that can genuinely improve the quality of life. If I have solutions I believe will work, I feel a responsibility to disseminate them. This is precisely why I embrace a "copy left" approach to design: sharing openly and allowing others to build upon these ideas. After all, solutions are never final; they continuously evolve as contexts change.