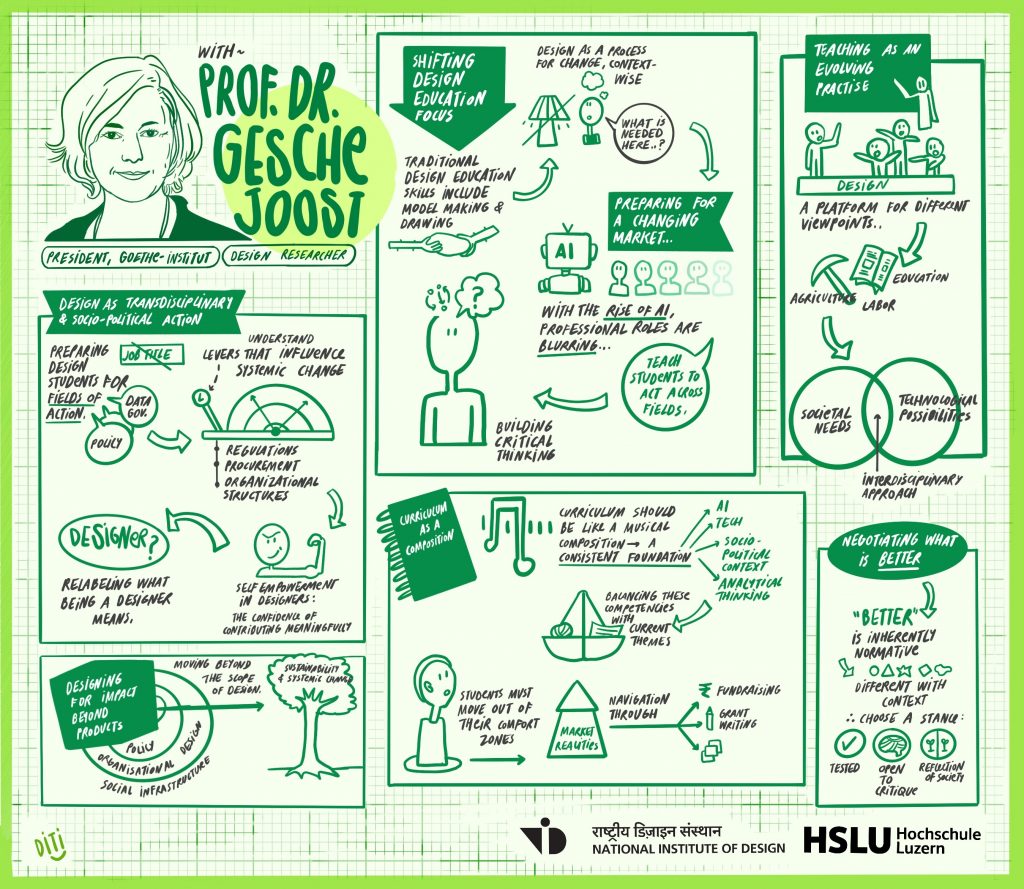

In this conversation, designer and researcher Prof. Dr. Gesche Joost calls for shifting design education away from fixed roles toward preparing designers to act across fields of change. We talked about education grounded in situations and needs, focused on literacies over static skills, and treating design as a process rather than a solution. She makes a case for cultivating critical agency, relabeling design beyond aesthetics, and identifying levers — from regulation to development — where design can have real structural impact. For her, curricula should be composed like music: with a steady foundation of tech, politics, and prototyping, and rotating thematic overtones that respond to the present.

From predefined outcomes to emerging needs

Gesche, you’ve been a design educator for many years, helping build design research in the German-speaking context and creating environments from which many relevant positions in socially engaged design have emerged. You also work across research and policy arenas where socio-political questions are negotiated. If you had to reshape design education today, what would you prepare people for?

Most schools still focus on skill delivery — model making, drawing, etc. But students graduate imagining a traditional design market that barely exists — and that many of them don’t even want. Design agencies are struggling, and the assumption that one beautiful product can both change the world and pay your bills no longer fits the reality. We keep producing single-author designers who are unprepared for collaborative, real-world contexts. GenAI and digital content in general is turning around the role of universities, too – from knowledge production and dissemination to engaging in a community of practice around global knowledge. We need to flip the logic: start from actual needs, then help students learn to teach themselves what’s necessary, project by project. I think the language of ‘literacies’ or ‘future skills’ is helpful here. There’s already substantial thinking at the European level about the mindsets and approaches needed to navigate change.

What does it take to reframe design education around this shift — from predefined outcomes to emerging needs?

Critical reflexivity is key: taking a stance through critical thinking and, from there, designing an intervention. This moves away from designing 'solutions' to engaging with design as a process for change. Changemaking feels like a big word, but it fits. Professional roles are blurring, AI is accelerating the shifts, and saying 'we educate product designers' feels outdated. Instead, we should ask: What’s my position in society? What’s my stance — politically, socially, technologically — and where are the openings for alternative proposals? That requires openness: not 'I’m going to solve this,' but 'I can initiate something and work iteratively, with others.' Transdisciplinarity is vital, and so is an international lens.

All of this is demanding. It requires mature personalities, people who want to change something. But 'better' is normative — it needs to be negotiated. That’s why you need a stance to test and expose to critique.

The point is not to kill ambition but to widen the imagination of where design work lives.

That connects to many discussions we’re having about future literacies. One figure that resurfaces is the ability to ask yourself what future you want — the normative dimension. Another thing we wrestle with is precisely what you said: the traditional jobs you were trained for don’t exist. As an educator, you end up in this in-between: we’re supposed to train for a market that isn’t there (yet), while a lot is demanded when graduates leave — finding a position where they can meaningfully contribute and make a living. What do you think we need to teach to make that possible? How do we make designing one’s career part of the design brief?

I think that’s crucial. In a way, we’re running on a pleasant fiction. Some of our student’s projects are still often about designing a new shelving system. And I think: what exactly is our picture of how designers will earn their living? You take your shelves to Vitra — is that the plan? Or material experiments: students think that because they mixed concrete with algae in their kitchen, they’ve invented the next super-sustainable material. The impulse to work with material is lovely, but overestimates what it can do. As art: great. As a livelihood or significant, systemic intervention: not really. So we end up with lots of solo self-employment, trying to sell shelves while surviving on tiny web jobs. That’s rough, because the potential is enormous.

The point is not to kill ambition but to widen the imagination of where design work lives: policy design, organizational design, standards, procurement, data governance, civic infrastructure. We must acknowledge the porous boundaries to politics, NGOs, management, etc. I see designers who could do great in management roles, could found NGOs, work on EU regulation. Designers are creative in rethinking alternative futures – and this is a competenciy that is crucial today in these times of poly-crisis. In the future, we will have to design our own role in society, too. And we have to be trained in digital tech, we have to deeply understand and embrace the power of AI, we have to engage with companies realities in order to embrace on a journey to support them. Therefore, we shouldn’t educate for profiles; we should educate for fields of action. And then look at the levers: what are they? If I want more sustainability, regulation is one of the biggest levers. It sounds boring, but it’s powerful.

Frames and Narratives

You’ve worked in places where designers supposedly don’t belong — boardrooms, policy councils, the presidency of the Goethe-Institut. Can you derive a teaching mandate from that? How do we prepare people to get into new arenas, hold their ground, and have an effect?

First, you need self-empowerment — believing you have something to contribute. And second: language matters. 'Designer' doesn’t automatically signal 'changemaker.' I was invited in as a researcher, or through the lens of digitalization. Those frames opened doors. So we need to think about our narratives — redefine its meaning and relevance. On a more pedagogical and strategic level, we should focus on helping students think systemically: Where are the nodes, what is my radius of action? Thinking in those terms seems more helpful than educational frameworks that build on lists of skills or job titles. Many students care about sustainability and climate change, which is one of the biggest challenges to humanity. Designers can play a vital role as change makers here – but the systems of decision making and of change are very complex. That is a good example of the dimension of change we are looking at.

That points to a broad, even universalist formation. What would you keep as anchors while staying responsive?

I like to think of the curriculum as a composition: the overtones (curated themes) change, and underneath there’s a basso continuo consisting, for example, of cultivating analytical and technological thinking, combined with socio-political, historical, and theoretical grounding, and a strong foundation in the craft of designing and prototyping. On top of that, you curate the triggers of the time — AI, questions of freedom, sustainability, whatever is salient. Not easy.

Reality Checks

Not at all; there are a lot of potential grounds to cover. We have students who want to work in agriculture, others in education, or in reinventing logics of paid labour. So we are iteratively building the structures that enable them to find their positions. One thing I’d like to push more is fundraising and grant writing: not just spin great ideas, but get them on the road. Most designers never learned that in design school. And I wonder how far our story that “the designer has a seat at the table” still carries — or whether we need to update it.

I’d also like more reality checks. Many highly motivated students are far from reality, sometimes afraid to go out into the world; they’d rather do another master’s to stay in a safe space. And they believe that a good product automatically equals economic success. That link isn’t automatic. Contemporary curricula need to include those really down-to-earth aspects: how things work, where money comes from, through which channels projects grow and mature. It’s a big balancing act: wanting to change the world and being pragmatic. But we need to achieve this balance if we don’t want to educate dream-walkers — who ultimately has to adapt to realities after art school and do something for a living that’s very different from what they had imagined in the safe space of academia.

About Gesche Joost

Gesche Joost is a design researcher and currently the President of the Goethe-Institut. She is a professor of design research at the Berlin University of the Arts, working transdisciplinarily at the intersection of art, science, and technology. Her research engages with the societal implications of digitalization and artificial intelligence, focusing on digital colonialism and growing global inequalities. From 2015 to 2018, she served as Germany’s Digital Ambassador to the EU Commission. She helped establish key institutions such as the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society and the Einstein Center Digital Future in Berlin. She is active on several advisory and supervisory boards, including ZKM, Ottobock, and ING DiBa.